November 23, 1997 | BRENDAN RILEY – ASSOCIATED PRESS | LATimes.com

BODIE, Calif. — Thanks to a buyout of old claims, modern strip mining won’t disrupt tourists’ reveries about life a century ago in this isolated town.

The $5-million deal means that quiet will prevail in what was once one of the wildest towns in the West–just what rangers at Bodie State Historic Park want.

Their goal is to keep the town in a state of “arrested decay.” That’s easier when the only sounds are weathered buildings creaking and rusted tin roofs rattling as wind sweeps across the treeless landscape.

Visitors–more than 200,000 every year–may wander the town’s dirt streets and peer through windows where whiskey bottles are still in the saloon, tables at home are set for supper and lessons are on the schoolroom chalkboard.

Specially trained carpenters have braced sagging buildings to keep them from collapsing and have rebuilt others so carefully that nothing looks new.

“We want people to look back and see what it was like 100 years ago or so–and I don’t know where you can experience that better than here,” says Walt Stone, a park worker. “We want people to appreciate what their forefathers went through, and to see how good they have it today–because life was not easy then.”

The solitude spooks some people, who ask about ghosts. Over the years, there have been stories of strange lights and music, of the ghost of a little girl killed by a miner’s pickax, and of the smell of garlic in the early-day Mendocini family home, where fresh-cooked Italian food was served years ago.

“I’ve been living here 11 years and I’ve never smelled any garlic–or seen any ghosts,” says Stone, standing outside the Mendocini home, where he lives during the summer. “But a lot of people see things, hear things, smell things.”

“There is a mood to this place,” he adds. “Probably the closest I’ve ever come is working on some of the buildings in the late fall, when nobody’s around. You start putting nails in some siding and you can feel something.

“It’s like, I want to do this really well and make no mistakes because these buildings almost have a life of their own. You can feel the presence of the people who lived here.”

The big threat to Bodie’s ambience was the possibility of renewed mining by Galactic Resources Ltd., a Canadian company that held rights to still-valuable claims. They started drilling for ore samples in 1989.

But the claims at Bodie, in the Sierra Nevada mountain range that divides California and Nevada, became available after Galactic went bankrupt in 1993. The company abandoned not only Bodie, but also a $60-million environmental cleanup at an old gold mine in Colorado.

State park officials had the opening they had long hoped for–although the deal wasn’t complete until this summer. The buyout doubled the size of the park to more than 1,000 acres. California put up $3 million and the American Land Conservancy put up $2 million, with the ALC to be repaid from federal sources.

The claims are spread over 515 acres on a bluff honeycombed with old mines. Also on the land above the town are the Bodie train station and about 50 buildings related to mining. They’ll be made part of the park that now includes about 150 homes, storefronts, a school, firehouse, jail, church, a big mill, cemetery, barns, sheds and outhouses.

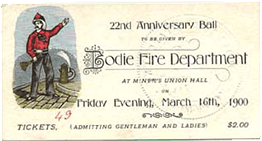

The town was named for William S. Body (pronounced BOE-dee), who found gold here in 1859. By 1880, there were 10,000 residents, 30 active mines and mills and about 600 buildings–including 65 to 70 saloons. Gambling, prostitution, opium and murders were common.

The mines produced bullion valued then at $70 million. With the gold came violence and vice, creating what one horrified preacher termed “a sea of sin lashed by tempests of lust and passion.”

A hint of the times appeared in a rival mining town’s newspaper. It told of a girl who looked skyward as her family packed, crying, “Goodbye, God. We’re going to Bodie.” Bodie editors challenged the punctuation, claiming she said, “Good, by God, we’re going to Bodie.”

With the mines played out and only a few residents left, Bodie folded in 1942 when a wartime law prevented gold mining. But a caretaker stayed on until 1962, when Bodie became a California park.

Harsh winters helped keep vandalism to a minimum. At 8,375 feet, Bodie often is hit by winds up to 100 mph, temperatures down to minus 35 F and annual snowfalls averaging 12 to 14 feet. Summers tend to be mild, although temperatures can change abruptly at high altitude. Last July recorded a low of 12 degrees–a clue about how tough things were and can still be.

‘We want people to look back and see what it was like 100 years ago or so. . . . We want people to appreciate what their forefathers went through, and to see how good they have it today–because life was not easy then.’

Walt Stone, Bodie State Historic Park ranger. At right, head frame atop a mine shaft in the old mining boomtown on the eastern edge of the Sierra. Below, a wagon outside the county barn. Although the town is quiet now, its history speaks to visitors. Even in September, bitter winds whip across the barren streets, chasing tumbleweeds and illustrating a story from the newspaper of a rival town in the 19th century: a girl who looked skyward as her family packed, crying, “Goodbye, God. We’re going to Bodie.”