Hard-luck town a tombstone for the wild West

by RUSTY COATS / McClatchy News Service / September 5, 1993

BODIE — At its peak, this Eastern Sierra mining town boasted 10,000 residents and 27 saloons, and blood flowed as freely as whiskey.

The town churches chimed the ages of the men killed in sidewalk gunfights and poker-room shoo-touts. Accounts from Bodie’s Daily Free Press said the bells rarely stopped ringing.

Bodie was a good town for undertakers.

Named for a man who died alone in a snowstorm, famous for its placer gold, horrible weather and gristle-tough reputation, Bodie was not a nice place to raise your kids. In fact, in 1880 a miner’s daughter in Truckee exclaimed: “Goodbye, God, I’m going to Bodie.”

Miners hauled millions of dollars in gold from her pits. Her stock shares soared from 50 cents per share to $45 per share in one year. Twenty years after W.S. Bodey discovered gold in the mountains north of Mono Lake, 10,000 people moved in, from miners and lawyers to gamblers, gunslingers and working women, who populated the red-light district, Bonanza Street.

Forty years later, Bodie was all but abandoned. By 1931, it was dead, its residents gone and its homes abandoned. And in 1962, it became a State Historic Park and, shortly after, a national landmark.

Bodie, once famous as the hottest gold prospect in California, stands now as one of the gold rush’s boom-bust casualties. Kept in a state of arrested decay, it’s a town-sized tombstone to the wild, dead west.

Located halfway between Bridgeport and Mono Lake on Highway 395, Bodie is a user-unfriendly tourist trap that draws 1,000 people a day between Memorial Day and Labor Day, according to Aaron Scarborough, a park aide at Bodie. Located an unlucky 13 miles off the highway, the last three miles are unpaved and liable to shake tailpipes loose.

Many of the visitors are German and French, who see Bodie as part of a California gold-rush package tour, Scarborough said, which explains why the historical accounts in the museum are printed in “Francais” and “Deutsch.”

“They get a lot of westerns on TV in Germany and France, I guess,”

Scarborough said. “They ask if John Wayne shot any movies here.”

He didn’t. Maybe because the Duke knew of the town’s luck.

Bodie is known universally —and through history — as a hard-luck town born under a bad sign. While placer-gold riches poured from its mines, black clouds were never far from Bodie.

The climate and topography remain God-forsaken. Built in a mountainous bowl at 8,305 feet, Bodie roasts at 105 degrees in the summers and snaps in the subzero winters. Snow whistled through holes and seams in the poorly assembled buildings. Bodieites used newspaper and packing paper for insulation. Firewood was a commodity almost as precious as gold, so precious that people hid dynamite in their woodpiles to blow the hands off Bodie’s infamous wood pirates.

Two fires devastated the town, halving it in 1886, then quartering it in 1932. Bullion guards with sawed-off shotguns were regularly sent to Charles Kelly, Bodie’s leading undertaker. And shootouts in the poker rooms of the Champion, Comstock, Aldridge and Senate saloons were more common than busted flushes.

Even Bodie’s successes couldn’t escape the whammy. Bodie saw the, world’s first hydroelectric power transmission in 1892, running from Green Creek to the Standard mine. In 1910, a hydroelectric plant in Jordan delivered electricity to Bodie, another first. But a year later, an avalanche destroyed the plant.

In the mines, though, the gold flowed. For a while. Production peaked in 1880, surged again in 1895 with a new cyanide process, then petered out in 1915, when most mines closed.

Now Bodie’s only residents are the park aides, some of whom live in Bodie year round in the Donally house, roughing the winters with a stack of videocassettes. And a steady flow of tourists wanders through the dirt streets, peering through dirt-caked windows and listening for ghosts.

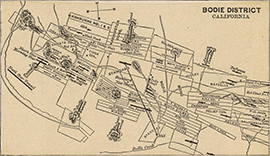

Popular spots include the town store, the busted-brick bank — destroyed in the ’32 fire — the mines and mills. Especially poignant is the cemetery, with its audacious granite and humble wood markers, and the museum, where you’ll find the caskets, photos, trinkets and artifacts of a dead town.

The streets are covered with their own souvenirs, from old glass and nails to an occasional coin. But park aides advise you not to shoplift in Bodie. Not because of any moral code, but because of the curse.

“People take old rusty nails as souvenirs and send them back,” Scarborough said. “They get them home and their luck goes bad. Just bad.”

As proof, he points to a table in the museum, covered with bits of glass and metal, lined with letters from people apologizing for looting, telling tales of bad luck — tax investigations, car repairs, fires and fights.

Scarborough, like Bodie, has little sympathy.

“With the reputation of this place,” he said, “they should’ve known better.”

Bodie, a California State Park, is open from 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. daily through Labor Day. Day-use fees are $5.