from Desert Magazine – November 1975 – by Roger Mitchell

IT HAD BEEN a bad winter, that winter of 1910-1911. Records amounts of snow had fallen in the Sierra. On a flat below 9,468-foot Copper Mountain in Eastern California’s Mono County, the turbines and generators of the Mill Creek Power Plant hummed a steady tune. The man standing the night watch over the dials and gauges of the plant’s main switchboard probably threw another log in the stove and wondered how long the blizzard raging outside would continue. Nearby in the employees’ quarters, seven others slumbered unaware of the terrible event about to happen.

Thus it was at 12:01 a.m. on March 7, 1911 when suddenly, without warning, the snow on the east face of Copper Mountain gave way, rushing down the mountainside in a huge avalanche. The Mill Creek Power Plant and its sleeping inhabitants were right in the path of a million tons of tumbling snow. There would be seven who never knew what hit them, but miraculously, one would survive.

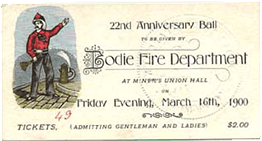

The outside world did not know of the disaster immediately. True, the electricity in the mining camps of Bodie, Aurora, and Luck Boy suddenly went off at 12:01 a.m., but that could be simply a line down anywhere in that lonely California-Nevada border country. The telephone lines had already broken under the weight of heavy snows.

As dawn tried to break through the wintery storm clouds, the snow continued to fall and the wind continued to blow Visibility was poor and the disaster would not be discovered for many hours. When the storm abated, the fate of the power plant was obvious. Where once had been four cottages and a concrete-housed power plant, nothing remained but a jumbled chaos of snow and debris. The avalanche left a path of destruction a mile long and a half mile wide. Generators and other machinery weighing tons were torn from their cement foundations and moved 500 feet downslope.

The word went out and soon rescue teams came in on skis and snowshoes from the nearby ranches. The Conway and Mattley Ranches served as headquarters for the search operation, keeping the men supplied with plenty of hot coffee and food as they probed through the snow in sub-freezing temperatures. One body was found and then another and another. The worst was feared.

It was a dog’s whimper that gave the rescue crews renewed hope. Digging frantically through the splintered wood which once had been cabin #1 they found a large steamer trunk was partially supporting a section of wall which had fallen over on the bed. Beneath the wall was the body of R.H. Mason. Next to him was his wife, Agnes and their dog, both miraculously alive, thanks to that

steamer trunk. After being extricated from the wreckage, Mrs. Mason was quickly evacuated to the nearby Conway Ranch, and from there taken by toboggan to the hospital in Bodie. She eventually lost a leg due to gangrene, but otherwise made a full recovery.The bodies of all seven victims were found and transported to the Mattley Ranch. They had to be stored there a few weeks until the roads were reopened and coffins could be brought in. Then, too,

the task of digging seven graves was a slow process because the ground was frozen solid. Finally a priest came in and the victims received a proper funeral and burial with people from all over Mono County attending.The Mattley Ranch is long gone, its site marked only by the bleached skeletons of cottonwood trees. The graves remain, however, on a lonely hillside overlooking the scene of the disaster. Every

now and then an old-timer from the area drops a flower or two on the seven mounds.The site of the tragedy seldom has visitors today, yet only a mile away hundreds of thousands drive by each year. Perhaps more would stop if they knew, but the story of the Copper Mountain avalanche is one of those brief moments in Western history which historians appear to think too insignificant to record for posterity. While the area is at an elevation of 7,000 feet, it is usually

accessible alt year around. Only after an occasional winter storm are the dirt roads impassable, and then usually only for a week or two.To make a short loop trip through the area, take U.S. Highway 395 to a point where it intersects with State Route 167, some seven miles north of Lee Vining, California. Continue north on 395 and

after 0.3 miles you will see a road on the left going to the new power plant, now operated by Southern California Edison Company. Do not turn )our loop trip ends here) but continue north on the highway another 0.4 miles, Turn left on the dirt road which goes down the embankment and through the unlocked gate in the highway right-of-way fence. After crossing the remains of the old highway, follow the dirt road as it winds its way westward through the sagebrush. Although vegetation has grown up between the tracks, the dirt road can be easily negotiated by standard automobiles. By keeping to the right you will come to a small wooden bridge spanning an irrigation ditch. This is 0.7 miles from the highway. Cross the bridge and park. This is the site of the old Mattley Ranch. Look for a faint trail heading east to the cemetery about 100 yards away.

Each of the seven graves is marked with a piece of gray-white marble reclaimed from what had been the power-plant switchboard. This stone panel once held all of the plant’s meters and controls, but like everything else in that building, it was torn to pieces.

To visit the site of the old power plant itself, follow the dirt road to the extreme left at the Mattley Ranch site. It heads back south paralleling the west side of the irrigation ditch. It is 0.9 miles to the site. Today, most of the debris is cleaned up but the site is still marked by concrete foundations and the remains of sections of huge steel pipes once part of the plant’s penstock.

To get back to Highway 395 continue following the dirt road which turns east. Within 0.4 miles you will come on SCE’s graded road and power plant. The main highway is but 0.6 miles beyond.

Desert/November 1975