November 1951 | by Lucius Beebe | Ford Times

Around 1908 the Ford Motor Company began printing a newsletter for its employees, but it became so popular, it was turned into a magazine for the public and featured submissions by popular writers like John Steinbeck and E. B. White, articles about places to drive in the United States and artwork and paintings by now well-known artists like Charley Harper. By the 1940s it was reduced to a 5”x7” publication that could ‘fit in a man’s suit pocket’. (Read more from Advertising Age Magazine)

As an advertising tool for Ford and their dealers, it reached a lot of people – and introduced those people to places they might never have heard of before… like Bodie, California.

Here is the November 1951 Ford Times article about Bodie. Click one of the images on the right to view or download the PDF and see the artwork of Bodie done by Harry Borgman and Parker Edwards.

by Lucius Beebe

paintings by Parker Edwards

Now and then in his Chronicles of frontier mining days in California and Nevada, Sam Clemens, who called himself Mark Twain, makes reference to “the bad man from Bodie.” On South Virginia Road outside of Reno there is a saloon tucked away between the motels called “Bodie Mike’s” in here and there elsewhere in the far west the uninitiated may come across some mention of Bodie and ask to know who or what is or was Bodie anyway?

So pass away the glories of the world.

In Bodie during its golden noontide of boom and bust, bonanza and borrasca, the wicked were like a troubled sea and salvation was far from them. When John Hayes Hammond, the great engineer and mining expert, spent a week there in the seventies, he reported that in that. There were six fatal shootings or stabbings, one for each day of the week with time out for the observance of Sunday. At the Bodie House where he put up he complained that the slugs from the revolvers of celebrants in the tap a room immediately below his chamber frequently penetrated his bedding and were generally an inconvenience.

Even the Sacramento Union, which kept close track of California’s more robust aspects of the time and was acknowledged a connoisseur of frontier excitements, admitted Bodie’s supremacy in the matter of tumults and remarked editorially with chamber-of-commerce modesty that Bodie was experiencing the “wildest, maddest years the West has ever known.” Bodie was outrageous with pride at the accolade.

The contemporary witticism which are rocked the West on its Congress gaiters was naturally attributed to bold, bad Bodie. When a minor in the neighboring but more tranquil diggings of Aurora was preparing during a temporary local recession to move his family down to Bodie it was reported that his little girl, when saying her prayers the last evening, addressed the Deity tearfully as follows: ” Goodbye God, we’re going to Bodie.” The wicked Bodie Free Press reported your sentiments but alleged there had been a mistake in punctuation. “Good, by God, we’re going to Bodie!” Was what the tot had really said.

From the very beginning Bodie enjoyed a macabre repute. The outcroppings of what was later to Esmeralda County were first discovered by a “Dutchman from Poughkeepsie” named William S. Bodie who, shortly after his contribution to Western legend perished in a snowdrift. His skull, discovered with the coming of spring and refurbished by local craftsmen, subsequently occupied a prominent position on the back bar of the Cosmopolitan Saloon.

Today Bodie and its twin ghost city, Aurora, are prize items among collectors of the souvenirs of bonanza towns of the old west. But, although all their fame is fully as effulgent as that of Deadwood, Tombstone, and Virginia City, not all today’s road maps show Bodie and Aurora. Rand McNally’s Road Atlas, for instance, shows only Bodie, but both are available to passenger automobiles either from U.S. 95 at Hawthorne, Nevada, and over Lucky Boy Pass, or from U. S. 395 about three miles south of Bridgeport, California, seat of Mono County. Bodie is in California, Aurora in Nevada, with the state boundary about equidistant on the canyon road connecting the two ghost towns.

Both are indeed ghost towns in the proper sense of the word, not as “ghost” is sometimes applied to such still inhabited though once populous communities as Central City, Colorado, or Tombstone, Arizona. Neither Bodie nor Aurora can list a single permanent resident although there is in summer a part-time caretaker who watches over Bodie’s tiny museum, and sometimes a line crew puts up in a well preserved home in Aurora while working on the high-tension wires which pass over the mountain there.

At a time when the fabulous earnings of the Comstock Lode a scant hundred miles to the north were making San Francisco a city of millionaires and helping to pay the Union expenses of the civil war, the cry “greater than the Comstock” possessed the magic which brought prospectors from all over the West. For a time Bodie was thus hailed by its more ardent exclamatory partisans, and the old staging roads of California and the high passes at Ebbet’s, Sonora, and Tioga boiled with the dust of immigrant wagons heading posthaste for the new Eldorado.

From the dubious estate of a “new diggings,” Bodie and its neighbor up the canyon, Aurora, passed almost immediately into the category of “proven camps,” which meant that their future instability were reasonably assured. All the conventional ornaments of a frontier community appeared overnight: the newspaper, a bank and half a score of false front hotels, and, of course, a multiplicity of plush gaming halls and saloons with central gas, plate glass mirrors, and big, economy-size spittoons.

Mine hoists sprouted in wonderful profusion along the slopes of Silver, Middle, and Last Chance Hills. Wells Fargo, the surest of all harbingers of bonanza took offices in the Windsor Hotel. Three breweries started operations: the Bodie, the Pioneer, and Pat Fahey’s, and were swamped with business. Opposite Wells Fargo was the town’s posh pub, the Philadelphia Beer Depot (” The Handsomest Saloon in Bodie and Patronized by All Classes. Sandwiches for Customers at all Hours.”).

No fewer than three newspapers: The Bodie Free Press, the Bodie Standard, and the Esmeralda Union started chronicling the gunfights and stabbings, and are yellowing files, happily preserved today in the Nevada State Library at Carson City, make brisk reading. In the first year of operation the Bodie graveyard boasted sixty-seven graves attributable two “sagebrush whiskey and poor doctors.” Bodie was one hell of a place and the fame of its wicked ways and spacious life was celebrated all over the world.

With great wealth daily being put into circulation from its reducing works, it was only natural that Bodie should attract the attention of a number of citizens who could by no stretch of fancy be termed law-abiding. The newspaper columns sometimes read like a bill of fare for hungry highwayman. “It looked like the old times in the Wells Fargo office Thursday night,” reports a yellowing issue of the Standard. ” there were ten leathern sacks, five from Bodie and five from Benton, wanting on the floor while three R and messengers with shotguns and self-cocking revolvers sat behind the counter.”

So frequently were bullion shipments being seized that Wells Fargo at length called in its most celebrated armed guards, Eugene Blair and Mike Tovey, to get the situation in hand. Secreting themselves on a midnight coach of the United States Mail Stage Company, they only emerged when the conveyance was held up by three masked miscreants just short of the Five Mile House. Wells Fargo’s answering blast of gunfire make formal identification of the three corpses out of the question and for a time the stages were as free from Allah station as in other and better ordered civilizations.

The mortality rate among gunman was so high in Bodie and when Wells Fargo was aroused that an undertaker in Virginia City was moved to lament the situation. “We never get any breaks in this business,” he moaned. ” as soon as the local talent gets to thinking they’re tough they try it out in Bodie and then the Bodie morticians get all the business.”

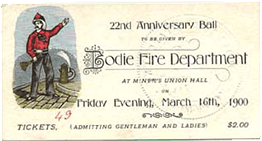

An The mines at Bodie supported a populous of 15,000 and a succession of bedlamite tumults for the next 30 years while an estimated $50,000,000 was recovered from its deep quarts mines and true fissures. Its golden noontide began to wane with the turn of the century but there were sufficient inhabitants as late as 1905 for a monster fireman’s ball, as is attested by the grand marshal’s ribboned badge of office visible today in the little Bodie Museum in what once was the Miners Union Hall.

The museum (which the caretaker will open for interested visitors if he can be discovered, which is usually possible in all that the worst part of winter) contains a variety of interesting evidences of the civilization that vanished with the “great fire” of 1932: bustled evening dresses and battered silk hats, typewriters of early Ordovician vintage, gambler’s derringers, and schedules of the several staging companies which served the district. It is not difficult for the imaginative intelligence to conjure up from these wistful souvenirs something of the florid in commotional past the once was Bodie’s.

Many of Bodie’s ones vital inhabitants are buried on the hillside, and in an adjacent cemetery, but removed from the holy ground, lie the remains of the town’s “fair but frail,” whose profession forbade their association, even in death, with churchly folk. At this remove such moral snobbishness seems no more than humorous.

The town’s hand-operated hose cart, which was of so little avail “great fire,” still stands in its station; the unpainted spire of the church points resolutely to the California skies and a series of regimented fire hydrants gives evidence of the town’s once impressive extent. The ruined vault of the Bank of Bodie, empty these many years of its minted double eagles, and standing alone amidst the ruins, has a sort of doomsday permanence about it.

Bodie as a rewarding an authentic ghost town for the amateur of the storied past, and once, in a world of mining excitements and sudden riches, its name bulked large in the mining security exchanges of the younger and probably happier United States.

Compliments of Heywood-Brunmark Motor Co., 301 Shrewsbury St., Worcester, Mass.

Front cover – Harry Borgman painted the “elephant” erosions in the Windows section of Arches National Monument, a spectacular natural attraction that lures many travelers to the eastern Utah.

“The FORD TIMES comes to you through the courtesy of your local deal to add to your motoring pleasure and information.”